-

-

-

Colonial Origins

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

About Falmouth - Colonial Origins

"A World on the Edge": From the Almouchiquois to New Casco

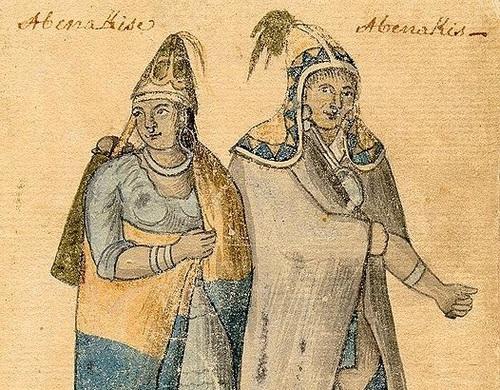

The history of Falmouth begins with the Native Americans who settled the region approximately 14,000 years ago following melting glaciers at the end of the last ice age. Archeological evidence suggests that agriculture first came to region between the years 1300-1400 CE. By the time French explorer Samuel de Champlain made European contact in the area in 1605, he identified the people living between the Androscoggin River and Cape Ann, Massachusetts as the “Almouchiquois.” Within the Almouchiquois, a semi-autonomous band Captain John Smith called the “Aucocisco” inhabited Casco Bay. English explorer Christopher Levett observed in 1623 that their leader (known as a Sagamore) Skitterygusset, resided at the Presumpscot Falls. The Almouchiquois suffered two tragedies prior to English settlement which has prevented scholars from knowing much about them. First, warfare with Micmacs to the north in a conflict scholars have later labeled the Tarrentine War brought defeat and death to southern Maine Indians. Second, an epidemic between 1616-19 claimed the lives of upwards of 90% of New England’s indigenous population. When the English began settling Casco Bay in the 1630s, only remnants of the Algonquian-speaking Almouchiquois remained in the area.

Falmouth’s early years were marked by extreme violence as it lay on a borderland zone between Europeans and Native Americans. Casco Bay represented the northernmost point of English settlement well into the 1700s. Powerful Abenaki tribes extending into French Canada lived to the west and north of Falmouth. Numerous wars between 1675-1763 among the English, French, and Native Americans rarely left Falmouth unscathed from the violence. The English twice abandoned Casco Bay altogether under pressure from French and Indian attacks in 1676 and 1690.

Falmouth’s early years were marked by extreme violence as it lay on a borderland zone between Europeans and Native Americans. Casco Bay represented the northernmost point of English settlement well into the 1700s. Powerful Abenaki tribes extending into French Canada lived to the west and north of Falmouth. Numerous wars between 1675-1763 among the English, French, and Native Americans rarely left Falmouth unscathed from the violence. The English twice abandoned Casco Bay altogether under pressure from French and Indian attacks in 1676 and 1690.

Arthur Mackworth was the town’s first European resident, building a house in the 1630s on the Presumpscot River. Later English settlers followed Mackworth’s example by settling on the Presumpscot, in close proximity to the bulk of English population on the peninsula known as Casco (now Portland). The borders of today’s Falmouth were known as “New Casco,” and was a village within the larger Casco settlement. The present Town of Falmouth would be known as “New Casco” until Portland separated in 1786.

Although the town was known as New Casco, it was during this early period that the name Falmouth first became associated with the area. In 1658 the Massachusetts Bay Colony took control of Maine, despite local resistance. Massachusetts renamed the Casco Bay settlements “Falmouth” after an important battle in the English Civil War which occurred in Falmouth, England. Massachusetts probably chose the name “Falmouth” to celebrate their conquest of Maine, symbolically mirroring the victory of Parliamentary forces over Royalists at Falmouth, England in 1646. Commonly known as “Falmouth on Casco Bay” to distinguish it from the Falmouth on Cape Cod, the original town boundaries included Cape Elizabeth, South Portland, Westbrook, Portland, and the current town

In an effort to improve relations with the local Native Americans, the English built a fort called New Casco in 1700 at the bequest of local Abenakis who desired a convenient place to trade and repair their weapons. The location of the fort would today be located opposite Pine Grove Cemetery on Route 88. A 1701 meeting between local Abenaki-Pigwackets and Massachusetts colonial officials cemented the alliance between the two peoples. A pair of stone cairns were erected as symbols of this friendship. The nearby Two Brothers Islands offshore later received their name from this long-forgotten monument. Unfortunately peace would not last as Queen Anne’s War broke out in the region two years later. The French sent Micmac, Mohawk, and French militia to raid the Maine coast and disrupt this new English alliance with the Native peoples of southern Maine. Massachusetts Governor Joseph Dudley traveled to New Casco in June 1703 in a vain attempt to keep local Native Americans out of the war. Six weeks later Fort New Casco was besieged by the invading Native American and French forces. The arrival of an armed Massachusetts ship saved the English huddled inside Fort New Casco. Peace returned in 1713, but three years later Massachusetts ordered the fort to be demolished. The destruction of Fort New Casco symbolized Massachusetts’ abandonment of their policy seeking the friendship of local Native Americans.

So long as the French controlled Canada, living east of the Presumpscot River in New Casco was a dangerous proposition. Only one family lived in the town in 1725. Growing English population and French defeat in King George’s War (1744-48) moved the borderland between Native Americans and English north to Midcoast Maine. By 1753 New Casco had grown to 62 families, and was large enough to form its own Parish. However Native Americans continued to target New Casco, most vividly witnessed by a raid in 1748 and the death of resident John Burnal in 1751.

The fall of Quebec City to the British in 1759 removed the French from North America, depriving nearby Native American groups of an important ally and formally ended the previous 130 years of unease or outright warfare in Falmouth. With the French no longer able to supply weapons for Native American resistance, little stood in the way of further English expansion into their territory. Local Native American populations had also been drastically reduced by disease, with most migrating north and west to join larger Native communities where they remain today. The colonial period had determined that the future inhabitants of Falmouth would be speaking English, not French or Algonquian.

Sources or further reading on this period of Falmouth History: for Native Americans, see Bourque, Twelve Thousand Years: American Indians in Maine (Lincoln, NE, 2004); Emerson W. Baker, “Finding the Almouchiquois: Native American Families, Territories, and Land Sales in Southern Maine,” Ethnohistory 51, no. 1 (Winter 2004): 73-100; David L.Ghere, “The ‘Disappearance’ of the Abenaki in Western Maine: Political Organization and Ethnocentric Assumptions,” American Indian Quarterly 17, no. 2 (Spring 1993): 193-207; for primary sources, see Christopher Levett, A Voyage into Nevv England, (London, 1628); Samuel Penhallow, The History of the Wars of New-England with the Eastern Indians (Cincinnati, 1859); Thomas Smith, Extracts from the Journals Kept by the Rev. Thomas Smith, ed. Samuel Freeman (Portland, ME, 1821); for general histories of the region, see William Willis,The History of Portland (Portland, ME, 1865); Emerson W. Baker, “Formerly Machegonne, Dartmouth, York, Stogummor, Casco, and Falmouth: Portland as a Contested Frontier in the Seventeenth Century,” in Creating Portland: History and Place in Northern New England, ed. Joseph A. Conforti (Lebanon, NH, 2005), 1-19.